| Benjamin Breckinridge

Warfield was born to William and Mary Cabell Breckinridge Warfield

in the rolling bluegrass country of Lexington, Kentucky, on

November 5, 1851. His father bred cattle and horses and was

a descendant of Richard Warfield, who lived and prospered in

Maryland in the seventeenth century. William also served as

a Union officer during the Civil War. Benjamin enjoyed both

the finances and heritage of the Breckinridges of Kentucky,

along with the prosperity and ancestry of the Warfields. His

mother’s father was the minister Robert Jefferson Breckinridge,

who was a leader of the Old School Presbyterians, an author,

a prominent Kentucky educational administrator, a periodical

editor, and a politician. The Warfields financial

prosperity enabled them to have Benjamin educated through

private tutoring provided by Lewis G. Barbour,

who became a professor

of mathematics at Central University, and James K. Patterson,

who became president of the State College of

Kentucky. L. G. Barbour wrote some articles

for the Southern Presbyterian Review

on scientific subjects and his own scientific interests may

have encouraged Benjamin in a scientific

direction. Ethelbert D. Warfield, Benjamin’s brother,

has commented that: |

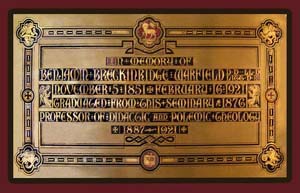

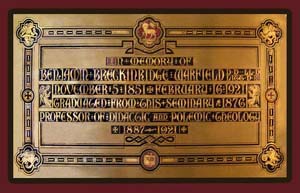

Dr. Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield

Dr. Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield |

His early tastes were strongly

scientific. He collected birds’ eggs, butterflies and moths,

and geological specimens; studied the fauna and flora of his neighborhood;

read Darwin’s newly published books with enthusiasm; and counted

Audubon’s works on American birds and mammals his chief treasure.

He was so certain that he was to follow a scientific career that

he strenuously objected to studying Greek. (page vi).

Following the years of private tutorial instruction, Benjamin entered

the sophomore class of the College of New Jersey (Princeton University)

in 1868 and was graduated from there in 1871 with highest honors

at only nineteen years of age. Having concluded his college years,

he then traveled in Europe beginning in February of 1872 following

a delayed departure due to illness in his family. After spending

some time in Edinburgh and then Heidelberg, he wrote home in mid-summer

announcing his intent to enter the ministry. This change in vocational

direction came as quite a surprise to his family. He returned to

Kentucky from Europe sometime in 1873 and was for a short time the

livestock editor of the Farmer’s Home Journal.

Benjamin pursued his theological education in preparation for the

ministry by entering Princeton Theological Seminary in September

of 1873. He was licensed to preach the gospel by Ebenezer Presbytery

on May 8, 1875. Following licensure, he tested his ministerial

abilities by supplying the Concord Presbyterian Church in Kentucky

from June through August of 1875. After he received his divinity

degree in 1876, he supplied the First Presbyterian Church of Dayton,

Ohio, and while he was in Dayton, he married Annie Pearce Kinkead,

the daughter of a prominent attorney, on August 3, 1876. Soon after

he married Annie, the couple set sail on an extended study trip

in Europe for the winter of 1876-1877. It was sometime during this

voyage that the newly weds went through a great storm and Annie

suffered an injury that debilitated her for the rest of her life;

the biographers differ as to whether the injury was emotional, physical,

or a combination of the two. Sometime during 1877, according to

Ethelbert Warfield, Benjamin was offered the opportunity to teach

Old Testament at Western Seminary, but he turned the position down

because he had turned his study emphasis to the New Testament despite

his early aversion to Greek (vii). In November 1877, he began his

supply ministry at the First Presbyterian Church of Baltimore, where

he continued until the following March. He returned to Kentucky

and was ordained as an evangelist by Ebenezer Presbytery on April

26, 1879.

In September of 1878, Benjamin began his career as a theological

educator when he became an instructor in New Testament Literature

and Exegesis at Western Theological Seminary in Pittsburgh. Western

Seminary had been formed by the merger of existing seminaries including

Danville Seminary, which R. J. Breckinridge, Benjamin’s grandfather,

had been involved in founding. The following year he was made professor

of the same subject and he continued in that position until 1887.

In his inaugural address for Professor of New Testament Exegesis

and Literature, April 20, 1880, he set the theme for many of his

writing efforts in the succeeding years by defending historic Christianity.

The purpose of his lecture was to answer the question, “Is

the Church Doctrine of the Plenary Inspiration of the New Testament

Endangered by the Assured Results of Modern Biblical Criticism.”

Professor Warfield affirmed the inspiration, authority and reliability

of God’s Word in opposition to the critics of his era. He

quickly established his academic reputation for thoroughness and

defense of the Bible. Many heard of his academic acumen and his

scholarship was awarded by eastern academia when his alma mater,

the College of New Jersey, awarded him an honorary D. D. in 1880.

| According to Samuel Craig, Dr. Warfield was offered

the Chair of Theology at the Theological Seminary of the Northwest

in Chicago in 1881, but he did not end his service at Western

until he went to teach at Princeton Theological Seminary beginning

the fall semester of 1887. He succeeded Archibald Alexander

Hodge as the Charles Hodge Professor of Didactic and Polemic

Theology. His inaugural address, delivered May 8, 1888, was

titled “The Idea of Systematic Theology Considered as a

Science.” As he taught theology, he did so using Hodge’s

Systematic Theology and continued the Hodge tradition. The

constant care Annie required and the duties associated with

teaching at Princeton, resulted in a limited involvement in

presbytery, synod, and general assembly. Annie lived a homebound

life limiting herself |

|

|

|

| primarily to the Princeton campus where Benjamin

was never-too-far from home. The Warfields lived in the same

campus home where Charles and Archibald Alexander Hodge lived

during their years at Princeton. |

Benjamin enjoyed a busy schedule at Princeton. One of his duties

at Princeton included editing the Presbyterian Review, succeeding

Francis L. Patton. When the Presbyterian Review was discontinued,

he planned and produced the Presbyterian and Reformed Review

until the Faculty of Princeton renamed it the Princeton Theological

Review in 1902. During his Princeton years he was awarded several

times with honorary degrees in addition to his D.D. including:

the LL.D. by the College of New Jersey in 1892, the LL.D. by Davidson

College in 1892, the Litt.D. by Lafayette College in 1911, and the

S.T.D. by the University of Utrecht in 1913.

|

After thirty-nine years of marriage, Annie died

November 19, 1915. She was buried in the Princeton cemetery

of what is now the Nassau Street Presbyterian Church with a

bronze, vault sized ground plate marking her location. Benjamin

continued to teach at Princeton until he was taken ill suddenly

on Christmas Eve of 1920. Until this illness, Dr. Warfield

had followed an active and busy teaching schedule into his seventieth

year of life. His condition was serious for a time, but he

improved enough that he resumed partial teaching responsibilities

on February 16, 1921. Despite not feeling ill effects from

the class he taught that day, he died of coronary problems later

that evening. He was buried next to his beloved Annie with

a similar marker for his grave. The Warfields did not have

any children. |

B. B. Warfield’s collected writings were massive, but he is

not known for writing a systematic theology and publishing books

was the exception rather than the rule; his writings were primarily

articles for periodicals, book reviews and notices, papers, pamphlets

and lectures. Sometimes his articles would be republished in pamphlet

or book form. His apologetic sense for responding to error in a

timely fashion most often led him to use scholarly journals and

other periodicals. Francis Patton’s memorial speech for Warfield

confirms this perspective as he commented that, “It was the

discussion of particular doctrine in connection with the most recent

phases of thought that he gave the greater part of his attention”

(“A Memorial,” 386). Some of Warfield’s chief concerns

included: the inspiration and authenticity of the Scriptures, perfectionism,

evolution, the history and theology of the Westminster

Confession of Faith, and the canonicity of the books of Scripture.

In connection with his interest in the Westminster Confession,

he had opportunities to write concerning revising the Confession

in both the 1880s and the early twentieth century. One area

of particular concern Warfield addressed frequently was defending

the New Testament against the German higher critics and their teachings.

Some have wondered why B. B Warfield did not publish a systematic

theology. Francis Patton’s perspective on this was that B.

B. Warfield believed Charles Hodge’s three volumes constituted

the best text for teaching systematic theology (“A Memorial,”

386f).

Some of the issues Dr. Warfield addressed are still contended today

including: deaconesses, issues related to the “Freedmen”

(i.e. African Americans), evolution, seminary curriculum, ministerial

education, baptism, the victorious Christian life, can dreams convey

revelation, and women speaking in the church. He also published,

in 1889, selections from Dr. John Arrowsmith’s Armilla Catechetica.

Warfield’s gifts included writing poetry and composing hymns,

including a hymn for the inauguration of Robert Dick Wilson as a

professor at Princeton Seminary. A short pamphlet of Dr. Warfield’s

hymns and poems was published by him titled, Four Hymns and Some

Religious Verses by Benjamin B. Warfield. Consistent with his

“Breckinridge” heritage, he wrote the biographical entry

for his grandfather, Robert J. Breckinridge, in Nevin’s Encyclopedia

of the Presbyterian Church. The readers of his works were not

limited to English speakers since some of his publications were

translated into other languages such as, “On the Antiquity

and Unity of the Human Race” (1911), which was translated into

Chinese, and “The Theology of the Reformation” (1917)

and “The Plan of Salvation,” (1915), which were both translated

into Japanese. Other works were translated into Dutch and Spanish.

The tremendously helpful bibliography of Warfield’s works by

James Meeter and Roger Nicole shows the diversity of his interests,

which included not only subjects of direct relevance to his discipline

but subjects of little or no relevance as well. One of his non-theological

interests was collecting postcards. In the early twentieth century,

the production of postcards was a growing industry that supplied

the new hobby of postcard collecting. The colorful, inexpensive,

and handy cards were used by tourists to inform their friends of

the progress of their trips and give them a glimpse of lands they

would probably not be able to see otherwise. Postcard collecting

was an activity that the Warfields could have enjoyed together,

though Annie may have had the greatest involvement in the collection

due to her homebound situation. Included in the collection are

cards from Switzerland, France, Italy, England, Kentucky, California,

Holland, Canada, Scotland, Germany, Pennsylvania, California, Mexico,

and many other places. One card was from C. D. Kinkead, presumably

one of Annie’s relatives, and it pictures the auditorium where

Calvin lectured on theology in Geneva. Another card shows Samuel

Rutherford’s grave marker in “Divinity Corner” at

St. Andrews Cathedral. There are several cards from Oxford University

picturing scenes from the various colleges. Another view is of

Luther’s study in the Wartburg, which was sent by “J.

C. Stout.” One card, postmarked 1908, shows the beautiful

old sanctuary and majestic steeple of the Independent Presbyterian

Church of Savannah, Georgia. Each of the cards collected by the

Warfields was placed carefully in its album and ordered according

to the part of the world from which it came. Whether the collection

of cards reveals Benjamin’s desire for further foreign study,

or Annie’s yearning to be free of her infirmity and travel

to the places pictured, or a combination of the two, are questions

that will remain unanswered.

B. B. Warfield was particularly prolific in publishing book notices

and reviews. Meeter and Nicole note in the preface to their bibliography

that they excluded over a thousand book reviews and notices that

were less than one page in length or judged of little interest to

the typical theologically oriented user of their book. Despite

these exclusions, the list of reviews show a diversity of subject

matter including: the personal life of the missionary David Livingstone,

ancient Egyptian life, the spiritual life of Charles Darwin, the

history of the Old South Church, plantation life before slave emancipation,

poetry, E. A. Poe’s poetry, Medieval book printing, Martin

Luther’s letters, monasticism and mysticism. The items excluded

by Meeter and Nicole included notices and reviews concerned with

architecture, novels, brain development and growth, sociology and

travel. Dr. Warfield’s academic efforts were often directed

towards issues concerning the Westminster Confession and

this is reflected in books he read about the lives of Westminster

Assembly members including Sir Henry Vane, Jr. and Alexander Henderson,

as well as books addressing the theology and history of the Confession.

Warfield’s intellectual capacity, diversity of interests,

and penetrating analysis could be placed at the apex of the scholarly

pyramid of his contemporaries. Consider the course of academic

events in his life. When he accepted the position in New Testament

at Western Seminary, the previous year he had already turned down

an appointment at the same institution to teach Old Testament.

When he went from Western to Princeton Seminary, he went from New

Testament to a position combining the disciplines of Systematic

Theology and Apologetics. When we consider that he was also known

for his historical studies on the background and editions of the

Westminster Confession, as well as the relationship between

Augustine and John Calvin, it is not going too far to say that he

could have qualified, in his era, as a one man seminary faculty

with abilities in Old Testament, New Testament, Apologetics, Systematics,

and Church History.

| When Benjamin Warfield died, there were notices, memorial

services, and eulogies in many parts of the nation. Warfield’s

own denomination, the Presbyterian Church in the United States

of America, adopted a statement at its General Assembly that

described his loss as “irreparable” and described

him as “probably the most distinguished and learned theologian

of the Reformed Faith in our day.” Following the adoption

of this statement, the Assembly heard a brief tribute to him

by President Kelso of the Western Theological Seminary, which

was followed with prayer led by President Landon of the San

Francisco Theological Seminary (Minutes, 128). In Dr.

Warfield’s home state of Kentucky, sentiments were expressed

in a special memorial service held in the Harbeson Memorial

Chapel of the Theological Seminary of Kentucky. During the

service each of the seminary professors, all of whom but one

had known him personally, spoke “tenderly of the man and

his great work and his abiding influence on every continent

of the world” (The Presbyterian 91:9, March 3, 1921,

31). One writer, known only as “G. P. D.,” wrote

of his three-year experience as a student of Warfield. He said

that one man stood out “above all others as a teacher and

as a man of God: and that man is Dr. Benjamin Breckinridge

Warfield.” Dr. Warfield had taught him to stand “solidly

upon the Rock of Ages” and he exemplified an “unswerving

loyalty to the Word of God.” |

|

The author also remembered Dr. Warfield’s continued instruction

to his students to seek the resolution of difficult issues by seeing

“what the Word of God says about that.” Showing his affection

for Dr. Warfield, the author mentioned that he and his fellow students

thought of him as “Bennie,” a name that would not likely

have been used in his presence (91:10, March 10, 1921, 10). J.

Gresham Machen, Assistant Professor of New Testament at Princeton,

received a letter from LeRoy Gresham, Dr. Machen’s cousin,

expressing in his own personal sorrow the sentiments of many regarding

the loss of B. B. Warfield:

You may well believe that I was inexpressibly

grieved and shocked at the death of Dr. Warfield. Truly there is

a prince and a great man fallen this day in Israel. Where shall

we ever find his like as a defender of the faith once delivered

to the saints? I know what it will mean to you personally, especially

at a time when the tendency is to fill our faculties with men who

represent a lower ideal of scholarship. It will be hard indeed

to fill his place. (Letter dated March 5, 1921)

Little did either LeRoy Gresham or Dr. Machen realize the prophetic

sense of this comment, for it would not be long before Dr. Machen

would become “a defender of the faith once delivered to the

saints” as he faced the modernist controversy.

Geoff Thomas has observed that Dr. Warfield died about three months

after the death of Abraham Kuyper and about five months before another

Dutch theologian, Herman Bavinck, passed away. The deaths of these

three signified the end of an era in the history of Reformed Theology.

Despite B. B. Warfield’s obvious significance, Mark Noll could

make the statement in 1999 in his American National Biography

article that, “There is no full account of either Warfield’s

life or his thought.” Anyone attempting to give a “full

account” of Dr. Warfield’s life and thought would be undertaking

a considerable task due to the depth, extent, and breadth of his

knowledge.

Sources Used:

Note: The letter to

J. Gresham Machen is in the Machen collection of the archives at

Westminster Theological Seminary, Philadelphia.

Calhoun, David. Princeton

Seminary: The Majestic Testimony, 1869-1929. Edinburgh: Banner

of Truth Trust, 1996. See particularly pages 313-327 for Dr. Warfield.

Craig, Samuel G. “Benjamin

B. Warfield.” At: http://www.graceonlinelibrary.org.

D., G. P. “The

Last of the High Calvinists.” The Presbyterian 91:10,

March 10, 1921. Pages 9-10. [The anonymous author responded to

an article from another publication in which Warfield was described

negatively as a “high Calvinist.”]

“Discourses Occasioned

by the Inauguration of Benj. B. Warfield, D.D. to the Chair of New

Testament Exegesis and Literature, in Western Theological Seminary,

Delivered on the Evening of Tuesday, April 20th, 1880,

in the North Presbyterian Church, Allegheny, Pa.” Pittsburgh:

Printed by Nevin Brothers, 1880. Includes the charge to Warfield

by Elliott E. Swift and Warfield’s inaugural address.

Four Hymns and Some

Religious Verses by Benjamin B. Warfield. Philadelphia: The

Westminster Press, 1910.

Hoffecker, W. A. “Warfield,

Benjamin Breckinridge (1851-1921).” Dictionary of the Presbyterian

and Reformed Tradition in America. D. G. Hart and Mark A. Noll,

eds. Downer’s Grove: InterVarsity, 1999.

Meeter, John E. and Roger

Nicole. A Bibliography of Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield, 1851-1921.

Nutley: Presbyterian and Reformed, 1974.

Minutes of the General

Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. New series,

vol. XXI, August 1921. Proceedings of the 133rd General

Assembly. Philadelphia: Office of the General Assembly, 1921.

Nichols, Robert Hastings.

“Warfield, Benjamin Breckinridge.” Dictionary of American

Biography. New York: Charles Scribners, 1946.

Noll, Mark A. “Warfield,

Benjamin Breckinridge.” American National Biography.

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Patton, Francis. “Benjamin

Breckinridge Warfield, D.D., L.L. D., Litt. D. A Memorial Address.”

The Princeton Theological Review 19:3 (July 1921): 369-391.

Roberts, Edward Howell.

Biographical Catalogue of the Princeton Theological Seminary,

1815-1932. Princeton: Trustees of the Theological Seminary

of the Presbyterian Church, Princeton, NJ, 1933.

Scrapbooks, 8 folio vols.

at the Luce Archives of Princeton Theological Seminary. These personal

collections contain postcards and newspaper clippings.

“Theological Seminary

of Kentucky.” The Presbyterian 91:9, March 3, 1921,

31.

Thomas, Geoff. “Benjamin

Breckinridge Warfield: If they Do Not Do What is Right, There May

be a Mighty Battle.” Banner of Truth web-site at: http://www.banneroftruth.

co.uk/articles/2001/11/benjamin_breckenbridge_warfield.htm.

Warfield, E. D. “Biographical

Sketch of Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield.” Works, vol.

1, Revelation and Inspiration, v-ix.

By Warfield:

[Note: Warfield’s

many writings were published in pamphlets, books, and periodical

articles over a period of many years. The 10 volume set of his

Works along with the 2 volume set on the shorter writings

provide the best collection of his work, but these two sets together

do not contain all his writings.]. For a comprehensive list of Warfield's

works, see A Bibliography of Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield,

1851-1921, by John E. Meeter and Roger Nicole (Nutley, NJ: Presbyterian

and Reformed Publishing Company, 1974).

Meeter, John E., ed.

Benjamin B. Warfield: Selected Shorter Writings. 2 vols.

Phillipsburg: Presbyterian and Reformed, 1970, 1973.

Noll, Mark A. and David

Livingston. B. B. Warfield: Evolution, Science, and Scripture,

Selected Writings. Grand Rapids: Baker, 2000. This contains

an article on Scripture, “The Divine and Human in the Bible,”

as well as thirty-nine articles, lectures, and reviews on the book’s

subject. This is one of Warfield’s more controversial areas

of thought because he accepted the possibility of evolution in some

form while denying Darwinism.

Warfield, Ethelbert D.,

William Park Armstrong, and Caspar Wistar Hodge, eds. The Works

of Benjamin B. Warfield. 10 vols. New York: Oxford University

Press, 1932; reprint, Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 2000.

About Warfield:

McClanahan, James Samuel.

“Benjamin B. Warfield: Historian of Doctrine in Defense of

Orthodoxy, 1881-1921.” Ph.D. dissertation, Union Theological

Seminary in Virginia, 1988.

Riddlebarger, Kim. “The

Lion of Princeton: Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield on Apologetics,

Theological Method and Polemics.” Ph. D. dissertation, Fuller

Theological Seminary, 1997.

Bibliography:

Articles appearing in The Southern Presbyterian

Review-

Dr. Edwin A. Abbott on the Genuineness of

Second Peter, 34.2 (April 1883) 390-445.

Some Recent Apocryphal Gospels, 35.4 (October 1884) 711-759.

The Canonicity of Second Peter, 33.1 (January 1882) 45-75.

Articles appearing in The Presbyterian Quarterly-

New Testament Terms Descriptive of the Great

Change, 5.1 (January 1891) 91-100.

Paul's Doctrine of the Old Testament, 3.3 (July 1889) 389-406.

Some Perils of Missionary Life, 13.3 (July 1899) 385-404.

The Constitution of the Seminary Curriculum, 10.4 (October 1896)

413-441.

The Doctrine of Inspiration of the Westminster Divines, 8.1 (January

1894) 19-76.

The Latest Phase of Historical Rationalism, 9.1 (January 1895) 36-67

and 9.2 (April 1895) 185-210.

The Polemics of Infant Baptism, 13.2 (April 1899) 313-334.

|